|

G.

Mark

Mulleian

and

Dean

Glassbrook

|

|

Freelance

writer

Dean Glassbrook

uncovers

hidden

secrets

behind

Mark Mulleian's

Paintings.

|

|

Dean

Glassbrook

grew

up in Orange

County California,

and in the early 1970s, moved to San Francisco as a freelance writer,

in order

to join

and explore

the gay underground.

The Disco Era was at its height and the earliest echoes of Stonewall

were just

beginning

to be felt

within the gay community. Dean was only

nineteen, and like most new arrivals, his exploration began at

the western

edge of

the Tenderloin,

among the many nightspots that thrived along Polk Street. Late one night,

after leaving one

of the

Polk Street

bars, wrapped in thought, he turned onto Pine Street, heading for home.

Upon turning the corner and heading

up the gradual incline from Polk, his preoccupied stride was about to

lead him past the Grub Steak Restaurant, when his

attention gravitated to the shimmer of a Moroccan coin necklace and

the glistening of a ruby gemstone fastened to the upper thigh of a pair

of Levis worn by Mark Mulleian. The eye-to-eye contact between the two

young men was immediate, and not without lasting consequences.

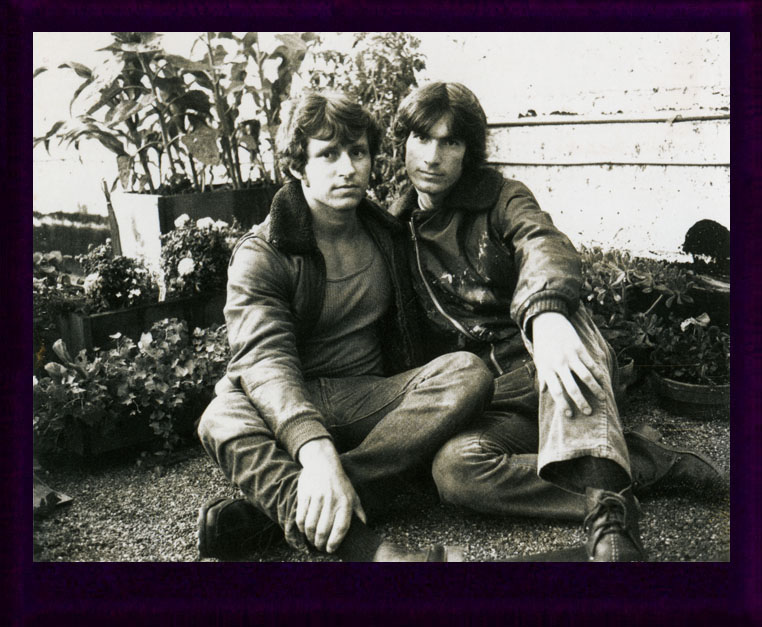

Because of that meeting, Dean would write and publish several insightful newspaper articles on the artist all through the late 1970s. Their relationship soon became intimate, and Glassbrook came to live with Mulleian at his studio, where they would spend three years together as intimate companions in a nourishing, mutually enriching involvement. Glassbrook met Mulleian at a critical point in the artist’s life. This engaging relationship led them to rigorous philosophical exchanges and flurries of critical thought touching on such subjects as the nature and management of economic structure, exploration of their reflections and feelings relating to a world of social and political issues, as well as an ongoing dissection of the composite features and limitations of intellectualism, including the use (illegitimate or otherwise) of linear thinking. Mulleian posits that for there to be a fully developed intellect one also needs to have an equal capacity for all three of the other functions of consciousness. That is, in addition to thinking, one needs to have feeling, intuition and the use of all the senses in order to fully apprehend reality. He believes that the byproduct of such a combination cultivates the overall creative process out of the depths of an enriched imagination. As a pair of playful conundrums to illustrate this proposition, Mulleian once wrote: “The

power of creativity is like a kiss of light upon the whisper of the

inner “If

one could shatter a sheet of glass without breaking it, At the time of first meeting Glassbrook, Mulleian knew nothing of Swiss Psychologist Carl Jung. It was not until many years later, when he met Paul Deegan, a student of Jung, that Mulleian realized the prescience of his own vision. Study of the artist’s work from a Jungian perspective reveals uncanny early examples of the use of some of Jung’s key theories, (such as the concept of Individuation as seen in Mulleian’s The Doorknob), in a panoply of symbolic imagery, palpable products of Mulleian’s intuitive process. In his earlier analysis of Mulleian’s work, Glassbrook would unintentionally scratch the surface of these issues. But Deegan, who came to study the paintings of Mulleian over four decades later, would further elaborate on Mulleian’s in-depth insights by uncovering the hidden nuances of symbols within his paintings. The artist’s intuitive use of this creative technique would have been a gem study for Jung to verify the spontaneous manifestation of elements of his own theories of aesthetics in mid-20th Century works of art if he were alive today. Throughout his work, there are many examples of Mulleian’s grasp of the Unconscious to be found in a wide array of what may at first appear as oblique, somewhat enigmatic images, but which serve, upon reflection, to illustrate his use of the intuitive process. Such images will invariably be understood to be symbolic, and be found, usually, to express an abstract complex of ideas in a surprisingly economical form. Typical examples of such images can be seen in the central forms of such early works as Stone Statue Epiphany and Stone Effigy. They may also be found in paintings produced much later in the artist life, images such as the eagle in Dies Irae, the disintegrating wire at the center of Calendar 2047, and the key and the telephone number here in this work, Spring Rain, to name just a few. During the three years of his relationship with Mulleian, Dean Glassbrook would devote much of his time studying both the artist and his work, discovering that Mulleian’s thinking demeanor was as rare and original as his painting. What made Glassbrook’s writing on Mulleian so unique were the insights gained through his personal relationship with the artist. The intimacy and intensity of their relationship while living with the artist s enabled Glassbrook a deeper perspective of Mulleian’s intellectual and emotional complexity. In the three years of living with Mulleian, Dean would quickly learn that the artist was not prone to conventional thinking; in fact, he would discover the artist and his art were one and the same. Dean focused more on the artist’s mental processes, his ideas, his conceptual approach to his paintings and the social commentaries they contained, as well as on the nature and direction of Mulleian’s thought while away from his easel. In an article published in the San Francisco paper Gay Crusader and in Mans Way, a west coast magazine in the late 70s, Glassbrook wrote: “Mulleian

is more then just an artist; he is philosophically imaginative. As an

obvious non-conformist, Mark's nature dictates the simple will that

he is nothing other than himself. Mark's greatest frustration is knowing

when he is not thinking his own originally constructed idyllic entities,

when speaking from a collective form of Non-physical status.” Glassbrook observed that Mulleian had an uncanny ability to use what he, Glassbrook, described as an “inversion observation” approach when making a point. This, he felt, was amply illustrated in many of the artist writings, and in a visual way, in most of his paintings. On the surface, Glassbrook saw the simplicity of what was being stated as provocatively deceptive. He found that as one is drawn to examine the words and phrases, or reflects on the juxtaposition of one image over another, one enters a stimulating world of mirrors, ultimately encountering meanings within meanings within meanings. Appropriately enough, another writer by the name of Dean Goodman, in a five-page article on Mulleian published in the west cost magazine In Touch, and the New Zealand Magazine OUT, also describes Mulleian’s style as “mirror writing”. As an example of this technique of expression, he sites an exchange between Mulleian and his life long friend, artist, photographer Jacques Andrian Javier, whose comment to Mulleian: ‘ I don’t believe in absolutes.” is met with Mulleian’s wry reply: “Is that an absolute?” This finely focused mirror response is typical of the artist’s gently reflective observation and playfully challenging thought process. His work is no less expressive of this reflective intention. Part of Mulleian's personal philosophy is summed up in another of his sayings: "I am my own student and this world is the university through which I may learn and translate". Glassbrook was very much aware of the reality of this statement, but at the same time, could not fully define the origins of the compelling force behind the paintings to expose it. The couple eventually separated in 1977. Later on, in the early 1980s, Dean returned to visit Mulleian once again. As he entered the studio, he noticed a small painting on the easel that Mulleian had been working on. Dean, who had long been aware of Mulleian’s clairvoyance, (as were many others who were close to him), rushed over for a closer look at the painting and saw within the painting’s composition a small snapshot photo of himself placed next to a card with a phone number written on it. Dean recognized the number. It was well known in the community at that time. It was the number for the AIDS Hot Line. Glassbrook immediately looked over to the artist with great concern and asked, “Does this mean I am going to die of Aids?” Mulleian, who had no knowledge of Glassbrook’s HIV status at the time, quickly but tactfully managed to change the subject. Two years later, when Dean returned one evening to meet with the artist for dinner at “Welcome Home”, a restaurant in the Castro, a sensitive and quite emotional dialogue took place between them. Dean revealed to Mulleian that he had AIDS. After leaving the restaurant, they joined hands and found their way to the intersection at Castro and Eighteenth Street. As they reached the corner, Mulleian stood silently watching as Dean crossed Eighteenth Street and gradually faded into the crowd. Dean died of AIDS two months later. Soon

after, Mulleian finished the painting on the easel and dedicated it

to the victims of AIDS. He called it Spring Rain. |