It

was at this time that two charismatic intellectuals

entered the artist’s life. The first of these was artist / photographer

Jacques Andrian Janvier, also known as Jacques

Lloyd. The second was Rebecca Campbell, a sister of the

Holy Order of MANS, a religious order founded in San Francisco by Fr.

Earl W. Blighton in 1960. Both Janvier and

Campbell would have extensive and ongoing influence on Mulleian’s

thinking and creativity, much as others have had before

and since. These include author Leonard Roy Frank, Benny Bufano, Thomas S. Szasz,

and later, Robert Arbegast and Paul Deegan.

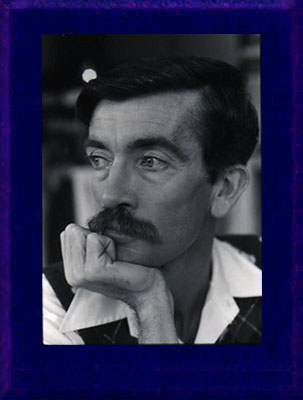

Jacques

Janvier first discovered

Mulleian’s work at the Frank Gallery in 1970. As artist and photographer,

Janvier was of French

heritage and had lived for awhile in Paris, Versailles, and the south of France,

finding unlimited subject

matter for his photography. Janvier was also a high caliber pastel artist and,

like Mulleian, a master technician himself. He frequented the gallery

over several months, drawn by a strong affinity to Mulleian’s work. Eventually,

in 1971, Janvier and Mulleian would meet, becoming lifelong friends and establishing

a relationship in which worldviews, political analysis, creative processes and

new ideas were shared in an inexhaustible dialogue for over thirty years.

By

1986, Mulleian had completed his painting Dies Irae, after two years of concentrated

work. Janvier had been looking forward to viewing Mulleian’s latest piece

ever since Mulleian first mentioned his ideas for the work at its inception.

Janvier had been so completely enchanted by Mulleian’s technique, (rightly

describing it as a lost art

no longer taught in art academies), he even asked the artist if he would teach

him to paint.

Came

the day for the viewing. The draped painting sat waiting on its easel in the

small humble cottage studio on the hill overlooking the beach. Janvier was an

imposing figure of a man, given to verbal eloquence on all manner of subjects

of the moment. He was an intellectual with an aristocratic demeanor and bearing,

as well as a broad-ranging grasp of American and European political history.

His grasp of the history of European and American art was extensive and impressive

as well, and some found his verbal manner and style to be undeniably intimidating.

In all, Janvier was a study in focused, elegant eloquence. This particular day,

he arrived with full cargo of topics to discuss, like a three masted schooner

in full sail, with no port in sight. But as the drapery dropped and the artist

stood aside to show the finished work, he saw the stunned Janvier catapulting

backward with the velocity of a cannon ball, hands abreast of temples, eyes

wide as onions, landing flatly, back against the cottage door. He was stunned,

literally taken aback by the sheer impact of the beauty of the piece. It wasn’t

long afterward that Janvier declared: “Mulleian is the New Old Master!”

Nevertheless,

for the several months that followed, the trio of friends, Mulleian, Janvier

and Arbegast, were at a loss as to what the painting should be called. Then,

one summer afternoon, Janvier returned to the studio with his friend Jean

Dennell, a notable watercolor artist herself. As it happened, Ms. Dennell’s

reaction to the work was virtually the opposite of Janvier’s. Her quietly

startled reaction took several minutes to find a voice. She, at first, seemed

overwhelmed by the painting’s powerfully dramatic message and technical

brilliance. Quietly, gradually, she moved ever closer to the canvas, intensely

studying every detail without saying a word. She was overtaken by the piece.

Dennell

was and is a deeply spiritual woman who had come from a Catholic background

and was most comfortable with the old, traditional Latin Mass. So it was as

though she had known the painting’s title before even seeing the canvas.

Out of what seemed like the silence of eternity, from under her breath and absolutely

without effort, came the words “Dies Irae”. To everyone’s amazement

and with a burst of exuberant relief, they suddenly realized the painting’s

name.

To

this day, nearly thirty three years later and at the age of nearly ninety, Jean

Dennell has never forgotten the enormous impact of the work, an impact which

hasn’t faded since she first laid eyes upon the artist’s easel, and

the painting of the day of wrath, which she named Dies Irae, one sunny afternoon

in August of 1987.